With autumn fast approaching, it will not be long before leaves start to fall and cool fronts bring us a reprieve from the Texas heat. While the change is welcome for some, this time of the year has inspired people for millennia to think about the cycle of life and death. To the Greeks, autumn and winter represented the half a year when Demeter, the goddess of agriculture, grieved that her daughter Persephone was confined to the underworld with Hades. The Pueblo people of North America have a similar tale about the Blue Corn Maiden (an entity who makes the corn grow) being locked away by the Winter Katsina (spirit) for six months out of every year.

Journeys to the Underworld

In their ruminations about death, many ancient peoples thought of the next world as a bleak and hopeless place. Some believed that all dead souls were sentenced to travel there no matter their deeds in life. And yet, several cultures across the globe have legends that share a common theme: a hero journeys to the underworld to either recover someone or consult a person who has died, struggles to get out alive, and returns to the world of the living with enlightened knowledge. Although these peoples were often separated by time and distance, we see this same story play out again and again in their myths.

In Greek mythology, Orpheus journeyed to the underworld to save his wife, Eurydice. Although cautioned that he could not look at her until they were both safely back to Earth, as soon as Orpheus set foot on the surface, he looked back to see if his wife was still behind him. Because she was still in the underworld, she could not leave, and so she was lost to him forever.

The Ashanti people of Africa have a legend about Kwasi Benefo, who made a journey to Asamando, the land of the dead, to seek the companionship of his four dead wives. On his way, he came across Amokye, an old woman who greeted dead women’s souls. She felt sorry enough for Kwasi to allow him into Asamando even though the living were not usually permitted to enter. When he found the souls of his wives, they told him not to be afraid to marry again and that they would be waiting for him when his time came to die. Kwasi fell asleep and awoke back in the mortal world, where he was finally able to come to terms with the deaths of his loved ones. After he remarried a fifth wife, he lived out the rest of his days in peace.

Chinese Buddhist tradition tells a story of a devout disciple of Buddha named Mulian. When Mulian discovered that his mother had died and was experiencing terrible karmic retribution in the afterlife for her sins, he went to the underworld to try and save her. All of his efforts were in vain, however, and so he appealed to Buddha for help. He was told that he must prepare a feast for the Buddhist monks on the fifteenth day of the seventh lunar month. With the monks interceding for her, Mulian’s mother was able to escape into a higher level of reincarnation.

And stories of journeys to and from the afterlife are not confined to ancient history. In 2017, Pixar released an animated movie called Coco about a little boy from Mexico named Miguel who accidentally finds himself in the Land of the Dead. He learns that this is where souls go, and stay, as long as there is someone left on earth who remembers them. He enlists the help of Hector, a soul who turns out to be his great-great grandfather, to get back home. In return, Hector wants Miguel to put his picture up on their family alter (ofrenda) so that he can return to the land of the living on Día de los Muertos (the Day of the Dead) to see his descendants. By the time Miguel returns home, he has learned the importance of putting family before personal desires.

A Unique Faith

Belief in an “afterlife,” or life after death, is overwhelmingly embraced throughout all peoples, cultures, and religions. And the widespread stories of journeys to and from an underworld, the realm of the dead, are a kind of mythological clue to the inner longings of the human spirit, implanted there no doubt by the one true living God.

What is distinctive about the Christian faith is our unusual belief in an embodied, physical life after whatever form the initial “life after death” takes. We believe that this kind of physical life is not a mere resuscitation from death or a near-death experience but is in fact an embodied existence, a joyful and unimaginably pleasurable and fulfilling existence, in a body like that of the resurrected Jesus.

Christ received a body, though one of a different kind, following his death and burial. In 1 Corinthians 15, Paul describes our current mortal bodies as like that of Adam but says our coming resurrection bodies will be glorified like that of our risen Lord. These bodies will be made of different “stuff,” though they’ll have a continuity with our bodies of this fallen and now corrupt creation.

Put another way, when we die, we lose the mortal body with which we are born, and, based upon the indwelling Spirit of God, a gifted consequence of belief in the gospel, we will receive upon Christ’s return a body like the immortal, resurrection body of Jesus. It is a body that, no longer subject to pain or death, can never die again.

And there’s at least one other important point worth noting about the distinctiveness of the Christian view. In New Testament teaching, death is not a friend that liberates us from our broken bodies. It is an enemy. It is contrary to all of God’s original intentions and, because of human rebellion, we are under a curse of corruption, mortality, and death. That divine curse was not the original intent, though it is now the universal fact for all of humanity. No promises of post humanism—the secular hope for an ongoing, everlasting life in these mortal bodies (or in some kind of hybrid stage of evolution brought about by quantum computing, artificial intelligence, or digital robotic technology)—can ever match the qualitatively different kind of body promised by the resurrection, including the promise that death itself, as the final enemy of humanity, will be defeated.

For the Christian, life is already on a hero’s journey, but it is a pilgrimage that someone has taken before us, someone who entered into our sphere of mortality and corruption and through death passed initially (albeit in his case, briefly) into the afterlife and then emerged on the third day into a glorious resurrected state. We follow him.

Special thanks to Angela Merkle for her contributions to this blog.

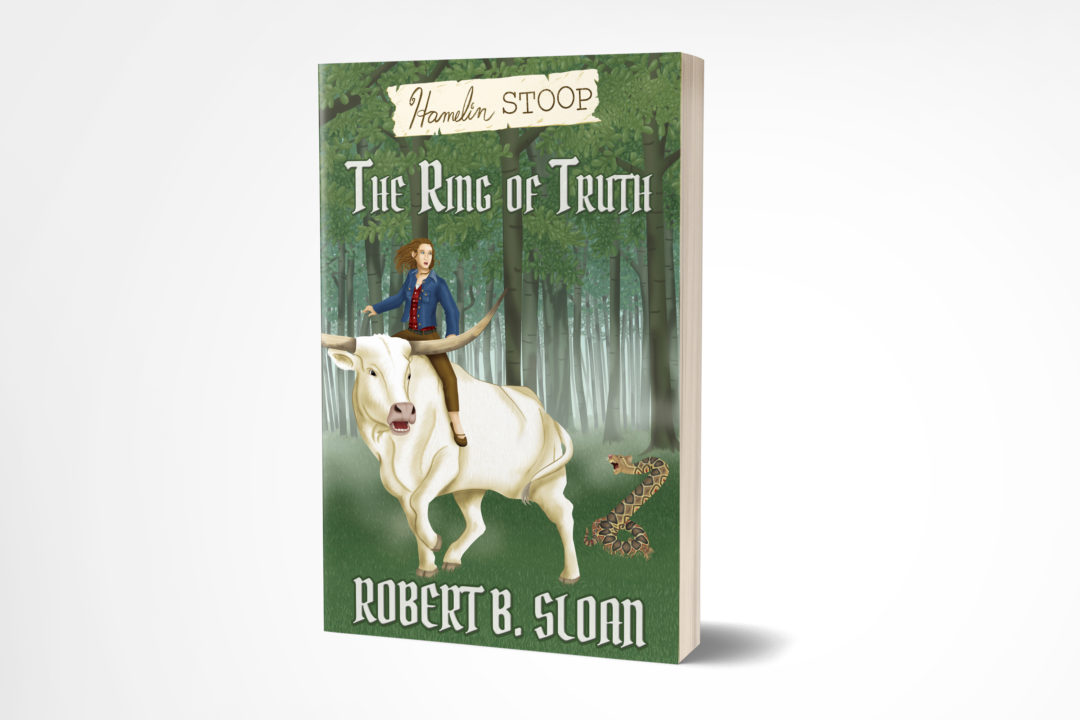

The hero’s journey is a major theme in the young adult fantasy series I’m writing about an orphan named Hamelin Stoop. The Ring of Truth, book 3 in the series, is now available.